Untitled | ngwaytayi (November, 1970)

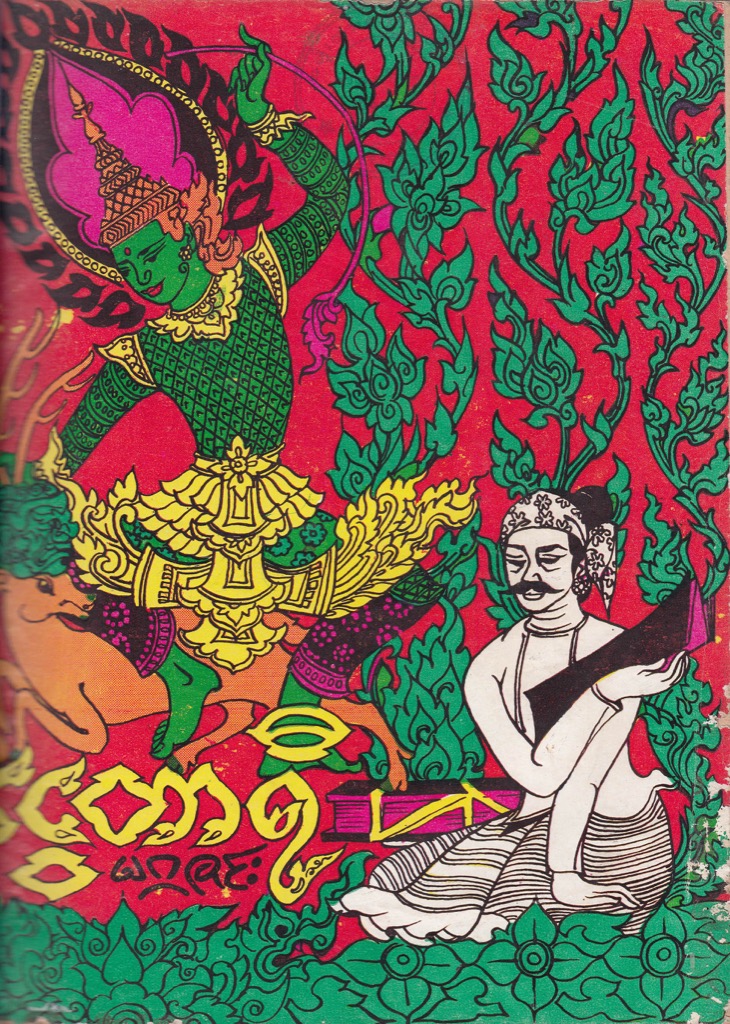

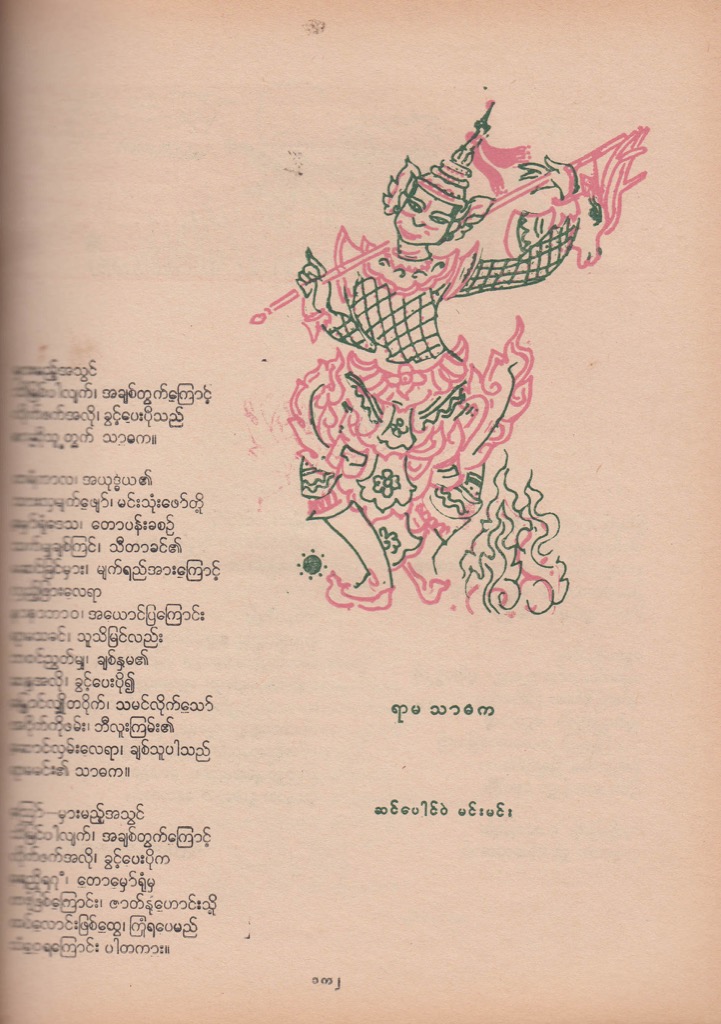

This illustration depicts the deer hunting episode from the Ramayana (Burmese: Yama Zatdaw), one of the two great Indian epic poems, which centres around the kidnapping of Rama’s (Yama) wife, Sita (Thida), by the demon Ravana (Datthagiri). Since its introduction to the Burmese people in the 11th century, episodes of the Ramayana are often incorporated into Burmese wood carvings, wall-hangings (kalaga) and lacquer designs. This particular episode of Rama hunting the golden deer has been among the most favoured by Burmese craftsmen. In a ploy to abduct Sita, Ravana orders the demon Maricha to shapeshift into a golden deer to attract Sita, knowing that Rama would chase after it at Sita’s behest, leaving her alone and vulnerable to attack. It is worth mentioning that although the Burmese and original Sanskrit versions share the same characters and structure (the former is based on the latter), the Burmese versions of the Ramayana are not merely translations or copies. They introduce new motifs, details and episodes which arguably add to the richness of the narrative.

The illustration employs a very graphic style with flat saturated colours and intricate line work. The green figure shown is Rama. He stands out against the red background. He has caught the golden deer after a troublesome pursuit through the forest and is about to slay it. He grips its antlers in his right hand and a bow in his left. This open stance with arms extended and the body gently arched sideways resembles traditional dance. The curved neck and antlers of the golden deer mirrors this lyrical movement. Instead of gold, a deep orange hue is used sparingly and only to colour the golden deer and Rama’s headdress, affirming his divinity as he is an avatar of the much revered Hindu God Vishnu.

A disc in the form of a large symmetrical stylised flower petal around Rama’s headdress further emphasises his divinity. This petal design is part of a long decorative tradition that has been applied widely, ranging from stamped pottery vessels to embellished stuccos on pagoda exteriors. Instead of naturalistic trees and bushes, the forest is depicted using htaunghatpan, a vertical floral and vegetal kanut ornamentation. Although highly stylised, it captures the vegetation’s dynamism: the leaf and petal forms taper upwards along sinuous vines, reflecting the skyward and organic growth of the trees. This method of expression seems in line with the mnemonic technique that Aung Soe was exposed to during his studies in Santiniketan. It involves first fully understanding a subject’s essence and vital rhythm before translating it using an appropriate visual language that is not limited to naturalism.

Amid the vibrant hues, a turbaned male figure sits in the bottom right corner of the work, drained of all colour. His pose accommodates and parallels the perpendicular corner of the image. Although seated, his pose is still dynamic, owing to his unique arm placement. He holds a parabaik or a folding book traditionally made of long strips of paper folded in an accordion style and used for writing manuscripts or business and administrative records. There is another parabaik bound with string behind him.

The three figures form a pyramidal composition with Rama at the peak. Compared to Rama’s theatrical and embellished costume, the man wears a simple everyday striped pah-so (sarong with folds in the front) and ein-gyi (fitting long sleeved jacket). They inhabit the same space but are visually disparate and do not seem to belong together. However, subtle spatial connections suggest they are in the same space. For example, the hind hoof of the deer seems to rest on the parabaik behind the figure. He also sits on a bed of four-petaled flowers which is joint to the kanut “forest” where Rama and the deer reside. These connections suggests that this is a stage in which this episode from the Ramayana is unfolding. The seated figure can be interpreted as the storyteller, reciting from the parabaik as the actors perform dialogue, song and dance. The mythical and physical world conflate in a single space. This illustration is characteristic of Aung Soe’s ability to skilfully rework beloved classical subjects.

Bibliography

- Aye Myint. Burmese Design Through Drawings. Bangkok, Thailand: Silpakorn University, 1993.Fraser-Lu, Sylvia.

- Fraser-Lu, Sylvia. Burmese Crafts: Past and Present. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Ker, Yin. “Modern Burmese Painting According to Bagyi Aung Soe.” Journal of Burma Studies 10 (2005): 83-157. Accessed April 9, 2016. https://www.academia.edu/5301730/Modern_Burmese_Painting_According_to_Bagyi_Aung_Soe

- Ohno, Toru. A Study of Burmese Rama Story: With an English translation from a duplicate printing of the original palm leaf manuscript written in Burmese language in 1223 year of Burmese Era (1871 A.D.). MinÅ-shi: ÅŒsaka Gaikokugo Daigaku Gakujutsu Shuppan Iinkai, 1999.

- U Thaw Kaung. “The Ramayana Drama in Myanmar.” Journal of the Siam Society 90, no. 1 & 2 (2002). Accessed April 9, 2016. http://www.siamese-heritage.org/jsspdf/2001/JSS_090_0i_UThawKaung_RamayanaDramaInMyanmar.pdf